By Jagpal Singh Tiwana

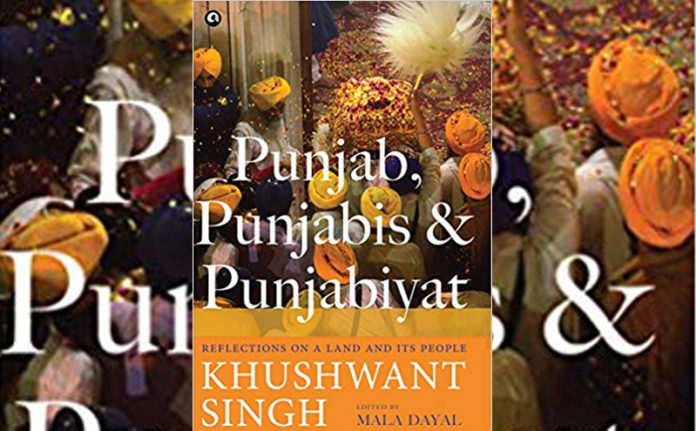

HALIFAX: Khushwant Singh’s best writings collected in the form of this book — Punjab, Punjabis & Punjabiyat — are just rivetting.

His daughter Mala Dayal, who has edited the book, says in the Introduction, “The pieces collected in this book are my father’s best writings on Punjab, its land and people…”

The book contains 31 articles in his trenchant style, loaded with sarcasm and humour.

Khushwant knew too much about people and incidents, and this book clearly brings it out. Most articles in the book consist of three or four pages.

His column “With Malice towards One and All” was most widely read in India. As usual, he doesn’t spare friends or foes alike.

His article on Maharaja Ranjit Singh gives a peek into the Sikh ruler’s queerness, governing style, and secularism.

He calls Bhagat Puran Singh a crackpot when the latter threw a few questions at him during his very first meeting with him. But then he goes on to praise Bhagat Puran Singh in the same article. “It was impossible to meet Bhagat ji and not feel inspired to contribute towards his mission in some manner, however modest…” and he did contribute.

Through his columns, Khushwant Singh persuaded many people to donate to the Pingalwara. He even talked to his siblings to make a substantial donation to the Pingalwara from the Sir Sobha Singh Charitable Trust. “In living memory, Punjab has not produced as great a man as Bhagat Puran Singh,” says Khushwant Singh.

In fact, he knew who are genuine humanitarians. That’s why he has kind words for Veer ji Tarlochan Singh of Delhi, Mother Teresa and Bhagat Puran Singh. Among politicians he likes Baba Kharak Singhj and Manmohan Singh.

Though Khushwant was a professed agnostic, his attachment to Sikhism and Gurbani is pretty obvious in the book which is divided into three parts.

Part 1 on ‘Punjab and Punjabiyat’ has 17 articles, 11 of which are on Sikhs.

Part 2 is on ‘My Bleeding Punjab.’ Four articles out of six relate to the incidents about 1984.

Part 3 on ‘Punjabis’ contains eight articles, with six of them focussed on important Sikh Punjabis.

His simple flowing prose and easy-to-read style keeps the reader glued to the book. His description of various events with great accuracy about places and dates brings great value to the students of history. Most of the events are eyewitness’ accounts where he is personally involved.

Khushwant was born at Hadali, a small village west of the Jhelum river, now in Pakistan. He grew up under the care and influence of his grandmother who was a deeply religious lady. “My grandmother spent her afternoons plying the charkha while mumbling Guru Arjan’s Sukhmani…” he remembers. This exposure to sacred hymns in his childhood had a lasting impression on him.

When Khushwant visited Hadali for the first time after moving to Delhi in his childhood, he was initiated into reading the Granth Sahib and advised to recite Japji Sahib daily. Later, he translated Gurbani into English which won him the admiration of the Sikhs. The translation Bara Maha of Guru Nanak is one of the articles in this book.

To write Sikh history was his ultimate desire. He said, “To write on Sikh religion and history was my life’s ambition. Having done that I felt like one living on borrowed time, at peace with myself and the world. It would not bother me if I wrote nothing else.”

His well-researched two volumes of `A History of the Sikhs’, written in 1963, was acclaimed as the best work on Sikhism in English. He was the first historian to introduce the Sikh religion to the western world.

Khushwant believed that Sikhism is an offshoot of Hinduism and he was worried that Sikhism would lose its distinctiveness as a faith and be absorbed by Hinduism.

His description of Akali politics is quite critical and forthright. He remarks that the Anandpur Resolution of 1973, drafted by Kapur Singh, is couched in most intemperate language and a product of confused thinking.

He is at his best when he describes the events of the 1980s and his views on those events are unmatched for their honesty and bluntness.

Despite his dislike for the Anandpur Resolution, he justifies the demands of Akalis. He says Chandigarh should be the exclusive capital of Punjab, waters of Punjab rivers along with dams and hydroelectric works belong to Punjab, and so do Abohar and Fazilka. Punjab needs heavy industry.

In one of his pre-June 1984 articles, he writes that if the legitimate demands of the Akalis are conceded with sincerity and grace, it will strengthen the hands of moderates and isolated Bhindranwale. Moderate Akalis should also show their loyalty to India. Separate nationhood will be suicidal for Sikhs.

However, the government was playing politics and using delaying tactics. Bhindranwale became stronger and popular among the Sikhs and Akali leaders started losing ground. Arms were brought into the Golden Temple in full view of the police. Whosoever, Sikh or Hindu, spoke against Bhindranwale, was eliminated by his men.

According to Khushwant Singh, up to May 1984, the government was not in favour of storming the Golden Temple to flush out terrorists, but the Akalis’ decision to bloc foodgrains going out of Punjab compelled the government to launch Operation Blue Star.

Khushwant is not probably right here because such an operation couldn’t have been launched without a preparation of several weeks or months. The government was planning to launch the surgical strike at a suitable opportunity and the blocking the foodgrains gave it the opportunity.

However, Khuswant Singh was not expecting the use of tanks and heavy artillery at the holy place. In his view, commandos in plainclothes and limited military action to occupy Guru ka Langar to deprive the terrorists of food, water and fuel was enough to force them out. This way, hundreds of innocent lives could have been saved and damage to the holy building avoided.

In protest, he returned the Padma Bhushan and earned the ire of Hindus and many journalists. “The reason why I was so upset by the army action is that it created a fertile soil for sowing the seed of Khalistan…I never have, not ever will, compromise with any move to dismember my Motherland. Khalistan will be made over my dead body.”

It goes to the credit of Manmohan Singh that Khushwant was honoured with the higher award of the Padma Vibhushan in 2007.

As usual, the book is not free from errors and omissions. Khushwant gives the population of Sikhs in Punjab after 1966 as 52 percent, whereas it was actually about 60.22 percent. He says that Guru Gobind Singh Marg is from Anandpur to Fatehgarh Sahib, but it goes all the way to Talwandi Sabo — a 577-km highway. He writes that the Singh Sabha movement was started in the 1890s but actually it began in the 1870s. Moreover, the article on Giani Zail Singh is quite complimentary, and it does not include his role in building Bhindranwale and his rivalry with Darbara Singh.

However, better figures and facts are given in the new edition of his `A History of Sikhs’.

Jagpal wirji, I just finished reading your review of The Sardar’s (for me Khushwant is a true, unafraid Sardar) memoirs by his daughter Maya Dayal. You, in the review have captured the true essence of what made him tick. He pulled no punches, spared no one, including himself.

Any idea how I can get this book to add to my “Sardar” collection ?

Keep up the good work wirji …jaggi